You might remember when, a couple of years ago, a group of students at a high school in Jerusalem produced a video for Purim that mocked Sephardi culture. Students in blackface acted out what their school would look and sound like “if the Ulpana were Mizrahi,” mocking their Mizrahi classmates with gross stereotypes of Middle Eastern Jews as loud, rude, and generally untamed.

The clip went viral, drawing consternation even from ministers in the Israeli government. The school issued a statement apologizing for the content, acknowledging that even though it was a parody for Purim, “it does not at all reflect what is happening at the school, which manifests itself in harmony and connection between different demographics in Israeli society.”

Teenagers do really stupid things. I did stupid things; you probably did as well.

As educators, when our students misbehave in ways that directly contradict communal values, we can easily default toward shaming the individual students and conveniently disengaging from the self-reflection their actions demand of us.

Student misbehavior, especially when it is at odds with a community’s stated morals and values, is also an opportunity for educator learning and self-reflection. We can lecture night and day about our community’s shared moral compass and values, but it is likely to fall on deaf ears unless and until our students are directly involved in a conflict that implicates these values. Likewise, our articulated shared values mean nothing unless and until they are tested and we use them as a rubric for assessing ourselves. Lessons, whether math or middot (character education), rarely stick outside the context of real-life application.

Rav David Menachem took a different approach. A unique Israeli rabbinic figure, Menachem is a Mizrahi paytan (composer of liturgical poetry) and an interfaith leader who has risen to prominence among Mizrahim and religious Zionist Ashkenazim alike.

He responded to this video, produced by students in the same high school his daughter attended, by encouraging his community of religious Zionists to hold up a mirror and reflect on the systemic issues that provide fertile ground for “bad apples” to grow, rather than distinguishing the specific group as outside the fold.

Effectively, he asked all of us, as educators, to reflect on how we contributed to the making of this video: “Our educational system is structurally racist. If the playlist is solely Ashkenazi, if interpretation of the Torah is solely based on the Ashkenazi — that is not only racist; it is a limited form of Judaism, and everyone suffers.”

I did not feel implicated in Rav Menachem’s rebuke about our schools as structurally racist against Mizrahim. This was not directed toward me. I’m all good. ”

As a Mizrahi Jew who heads a primarily Ashkenazi Jewish day school, I considered myself better equipped and more obligated to dismantle this sort of systemic prejudice and cultural ignorance, because I am more attuned to it by the nature of my personal identity and experience. I feel a deep responsibility to raise our children in a school community that normalizes and celebrates multiculturalism and breeds respect and connection across differences rather than overt contempt or, more likely, latent but powerful racism. I did not feel implicated in Rav Menachem’s rebuke about our schools as structurally racist against Mizrahim. This was not directed toward me. I’m all good.

However, the second part of Rav Menachem’s response landed like a direct and personal rebuke. He asked the Mizrahim in school communities to confront their role in the systemic racism from which this video sprouted:

We must stop playing a cultural role for the Ashkenazim. We have turned ourselves into entertainment and folklore, because we don’t know anything about our own culture. Judaism in Morocco dates back 1,500 years, and all we show here is our special foods and rhythms? Is that all we have to offer — taste and smells and sounds? What about our sages and our traditions? In an attempt to ingratiate ourselves, we have turned ourselves into vulgar stereotypes. We must not undervalue ourselves. We must hold our heads high. That must be our response to this video, and to what it represents.

Wow. This indictment was directed toward me. It made me ask whether I am contributing to what he describes as “entertainment and folklore” through my acts of omission. I believe that fluency education and identity education are closely intertwined. Neither one alone makes for a strong, resilient Jewish future. Yet, I’ve forgone the fluency piece altogether with respect to Mizrahi Judaism. I don’t think I have developed a mature and deep understanding of my own Mizrahi texts and traditions.

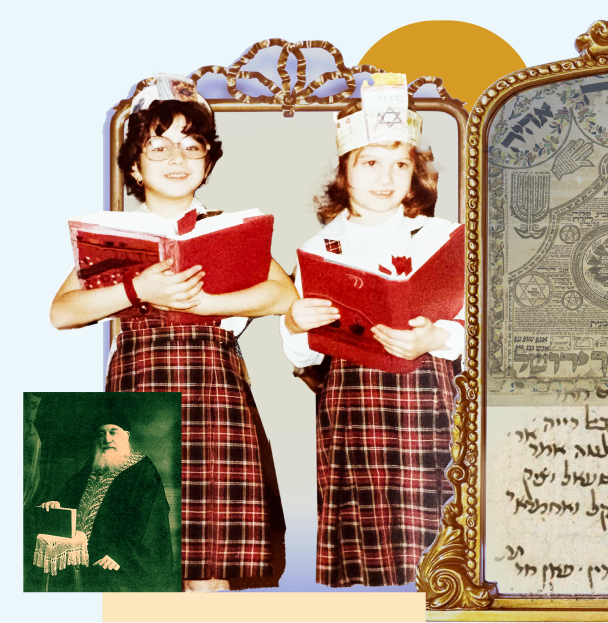

I grew up in Los Angeles with a Baghdadi father and a Tunisian mother in a family and synagogue community that was a diverse mix of Sephardi and Mizrahi Jews who tightly held on to their families’ heritages linguistically, liturgically, and culinarily. Family members spoke various dialects of Arabic at my own Shabbat table; we ate couscous and mechshi (North African stuffed vegetables) on Thanksgiving, and we visited hahamim (the common Sephardi term for rabbis of high stature) for blessings.

My siblings and I, however, attended an Ashkenazi Orthodox day school down the block from our house, and it provided the spark that led my parents to more rigorous halakhic observance, or shall we say, “frumkeit.” As a result, my textual fluency is Ashkenazi. I learned to read Torah with an Ashkenazi sing-song tune, studied only Ashkenazi halakha, and grew up on Chassidic stories. I never studied Jewish texts with a Mizrahi teacher until I met Rabbi Daniel Bouskila while I was studying in yeshiva for a couple of years after high school. In fact, my story tracks the common phenomenon among Mizrahim who lean into stringent Orthodox observance, where becoming “more religious” looks like becoming “more Ashkenazi.”

My Jewish history education was also European-centric. Growing up in the 1980s and 1990s, all Jewish history lessons started or ended with the Holocaust. Yet, it was only this year, at age 49, that I realized my own family members were victims of the Shoah: my mother’s maternal grandparents were interned in Tunisia and her paternal grandparents were interned in Libya, not to mention my uncle who hid during the war as a Catholic in the French countryside.

I had heard bits and pieces of these stories, but I didn’t process them as a personal family connection to the Holocaust. I suspect this is because we did not speak about Sephardim in all the lessons on the Shoah, so we effectively learned that the Holocaust didn’t come for Sephardim.

Outside of school, in my youth movement, the history of Zionism focused on the great religious Zionist leaders of the 20th century, “gedolei hador” like Rav Avraham Yitzchak HaCohen Kook and pioneers who founded the few but mighty religious kibbutzim. I was aware of the lack of Sephardi history and intellectual tradition in my education as a child and was never happy about it. I always longed for the depth of connection to Mizrahi Jewish intellectual life that my parents described from generations past: the great hahamim and kabbalists in our family history, and the many ancestors who lived in a seemingly peaceful intersection between their Jewish particularism and their broader societies. But I didn’t do much to address this frustration or longing.

By the time I married a wonderful and Ashkenazi man in my early 20s, I had already begun moving away from mainstream Modern Orthodoxy and toward an egalitarian-informed Judaism. We combined our traditions to take the best of both. I reduced my wait time from six to three hours between eating meat and milk, and he started eating kitniyot (legumes prohibited to Ashkenazim) on Pesach – everyone wins! He learned my mother’s North African recipes for Shabbat and holidays, and it turns out he can make a mean chraymi (a spicy fish dish common in North African cuisine). Each of our children has two names, one for a deceased relative of his and one for a living relative of mine, according to our respective traditions.

At the same time, my prayer and intellectual communities became increasingly more distant from Mizrahi Judaism as I moved toward the niche world of Conservadoxy. The unintended and seemingly unavoidable consequences of my Jewish decisions in adult life exacerbated the dichotomy that displeased me: it seemed like carrying on a tradition without engaging in any rigorous analysis or understanding of the Mizrahi Jewish canon. While I tried to maintain many Mizrahi traditions, I increasingly did so with less intellectual depth.

This is why Rav Menachem’s rebuke stung. Is it possible that I perpetuated these vulgar stereotypes with my blowout henna ceremony a couple of days before my wedding, my ululations at semahot (celebratory occasions), my insistence on greeting students with the distinctly Sephardi response of “hazak u’baruh” (strength and blessing) at their in-school bene mitzvah? I have not learned our history the way I know “mainstream” Jewish history. I have not studied our philosophy the way that I have studied “mainstream” Jewish philosophy. I have not thoroughly explored our halakhic sources in the same way I have read “mainstream” halakhic sources. I do not speak any version of Arabic. I do not pray in Mizrahi tradition. However, I do lay tefillin in the tradition of my father and his father before him, but as a woman, this feels like a break with Sephardi tradition as much as it does a continuation.

I am committed to building a school and community culture that does not breed performances like the one from the girls in Jerusalem. I agree with Rav Menachem that this goes beyond asking Ashkenazim not to be racist. It requires Sephardim in Jewish education, especially leaders, to look in the mirror and ask whether we are contributing to the simplistic view of Sephardim that is mocked in this video.

I always longed for the depth of connection to Mizrahi Jewish intellectual life that my parents described from generations past: the great hahamim and kabbalists in our family history, and the many ancestors who lived in a seemingly peaceful intersection between their Jewish particularism and their broader societies. But I didn’t do much to address this frustration or longing. ”

I have a problem, as does our field of American Jewish education. How do we move in this direction of deep integration of Mizrahi Judaism in our Jewish day schools, the sort of authentic presence and belonging that clearly did not exist in the community from which the parody video arose? How do we do this as individual leaders without investing in a rigorous graduate-level education in Mizrahi texts, law, prayer, and tradition? If this is unrealistic for me, I suspect it is even more unrealistic for my Ashkenazi colleagues.

The answer is the same as for all daunting, adaptive challenges. Leaders have to find the tools and frameworks that empower them against the pull of debilitation.

There are easy steps that any educator can take. Identify the staff and families with Sephardi and Mizrahi identities and find opportunities for them to share their family history and traditions on the obvious holidays, like a Rosh Hashanah seder, and on the less obvious, like Yom HaShoah.

Resources are available, too, at little to no cost. Audit your classroom libraries and make sure the Jewish books reflect the wealth of our diverse Jewish backgrounds. Highlight Sephardi and Mizrahi stories even if, and maybe especially if, your community is primarily Ashkenazi. PJ Library will happily send you a wealth of resources. The simple act of a teacher reading these books will broaden some students’ perception of the Jewish people and ensure that others see themselves as represented in the community’s perception of Jews.

Take the next step and update your curricula. Start by scanning your social studies and Jewish history curricula across grades, and add Mizrahi history and literature, whether students are studying the American Revolution or modern Zionism. Now we also have the benefit of JIMENA’s Sephardi & Mizrahi Education Toolkit, an off-the-shelf curriculum and fantastic new resource for all Jewish day schools.

Other steps require a level of fluency that educators in a particular school lack. For some, integrating Sephardi and Mizrahi teshuvot (responsa literature) into halakha classes or reimagining an entire Jewish music curriculum can be daunting.

In that case, what might it look like for teachers of Jewish law to choose a selection of Rav Ovadia Yosef’s teshuvot to study together over the year for their own learning — lishmah, for its own sake — without the pressure of reimagining their curricula. What if Jewish music teachers gathered in one school or across schools to study piyyutim with one of the next generation Sephardi paytanim or paytaniot?

So many opportunities are ready to be deployed to advance meaningful Mizrahi belonging beyond platitudes and light entertainment. They are accessible to people who are not fluent in the texts and traditions of Mizrahi Jews, whether it is because they are Ashkenazi or, like me, lack fluency in their own tradition.

At the same time, Mizrahi texts and tradition will likely continue to represent a minority identity in our American Jewish day schools, and so, we will continue to confront incidents of prejudice no matter how much proactive work we do, even when we go beyond shallow representations. As educators, we all know how to respond to these incidents. Irrespective of our backgrounds or fluency in different communities and traditions, we know that student misbehavior is an opportunity for growth — theirs and our own.

It would have been pretty cool to lead the girls who made this Purim video through a process of reflection and an opportunity to repair the harm they caused. In fact, this sort of misbehavior is a gift to the students’ educators and the school’s leadership. It provides an opportunity for relevant and meaningful learning and growth for the individual students and the community more broadly.