I wrote Shoham’s Bangle from a deep wish to tell the story of my Iraqi Jewish grandmother’s turquoise bangle — the one I wear today. It jingles on my wrist the way my grandmother’s bangles jangled. She wore a whole musical stack. Her bangles jingled as she baked and cooked Iraqi Jewish food and clapped her hands to Iraqi Jewish songs. They knew a story I wanted to tell. The story my grandparents never told me. Why they, and over 120,000 Jews, left Iraq between 1950 and 1952.

Today, only three Jews live in Iraq. I was very close to my grandmother, and yet I didn’t really know that she was born in Al-‘Uzair, by the grave of Ezra the Scribe. I didn’t know that she moved to Baghdad after marrying my grandfather. I didn’t know that a third of Baghdad was Jewish in 1917. I didn’t know anything about her life there. But the bangle knew.

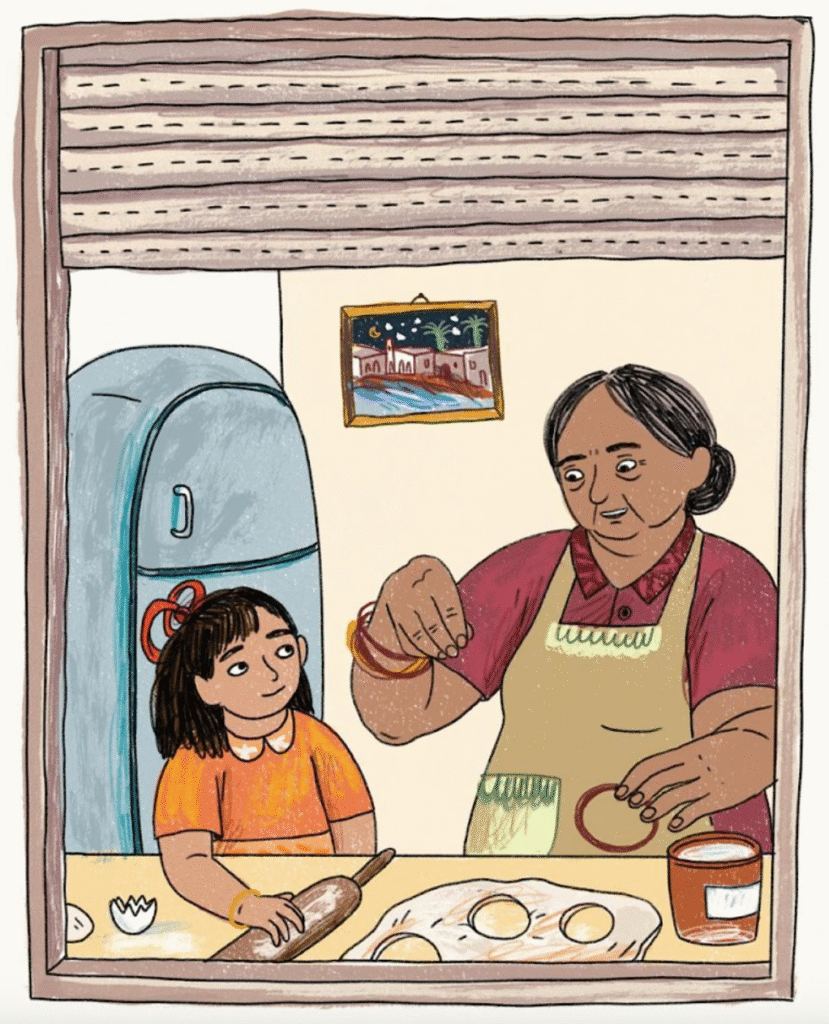

I sat to write the bangle’s story, and I wrote everything I had grown up with, and everything I had researched about Baghdad. I wanted to capture what my grandmother would say — that life there was beautiful, like the Garden of Eden. I wanted to capture my own joy and connection to her through the bangles, and the closeness between Shoham and Nana as they baked ba’aba tamar date cookies together and picked figs and shared their bangles’ magical rememberings.

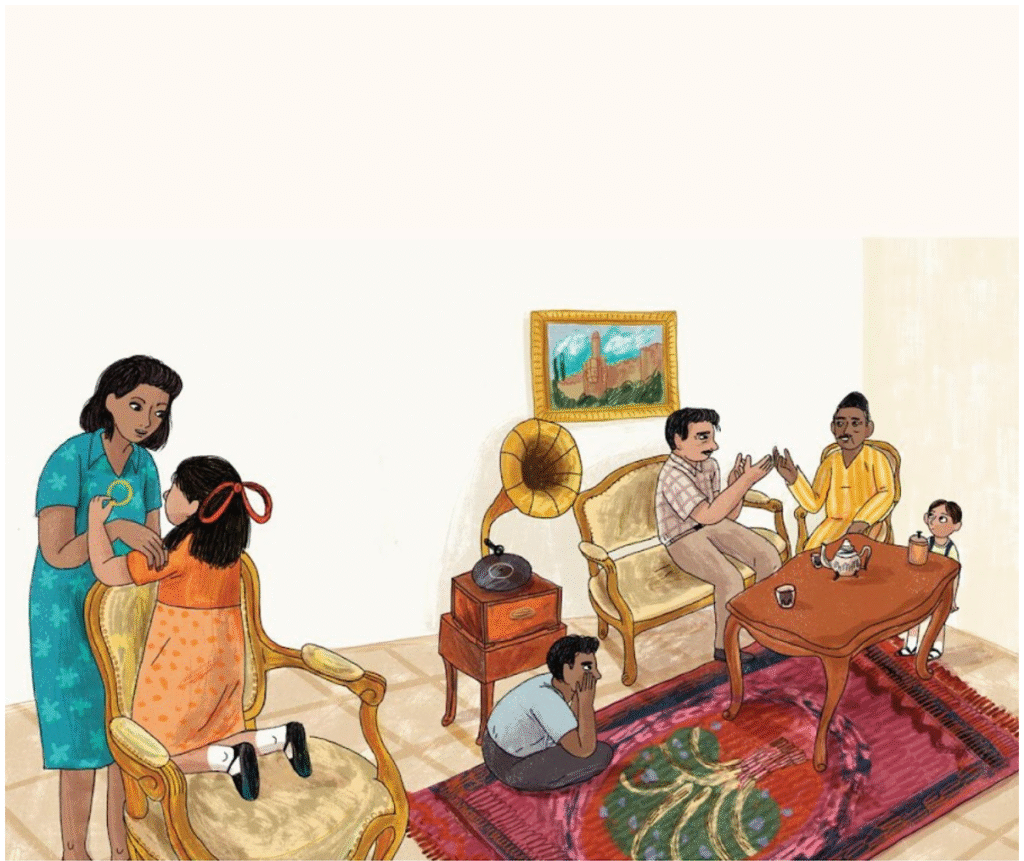

I was worried that whoever illustrated Shoham’s Bangle wouldn’t understand how modern and educated Iraqi Jews were in Baghdad in 1950. I sent a whole file of photos of my family and Iraqis dressed in modern clothes and bangles and examples of the food to Joni Sussman at Kar-Ben Publishing.

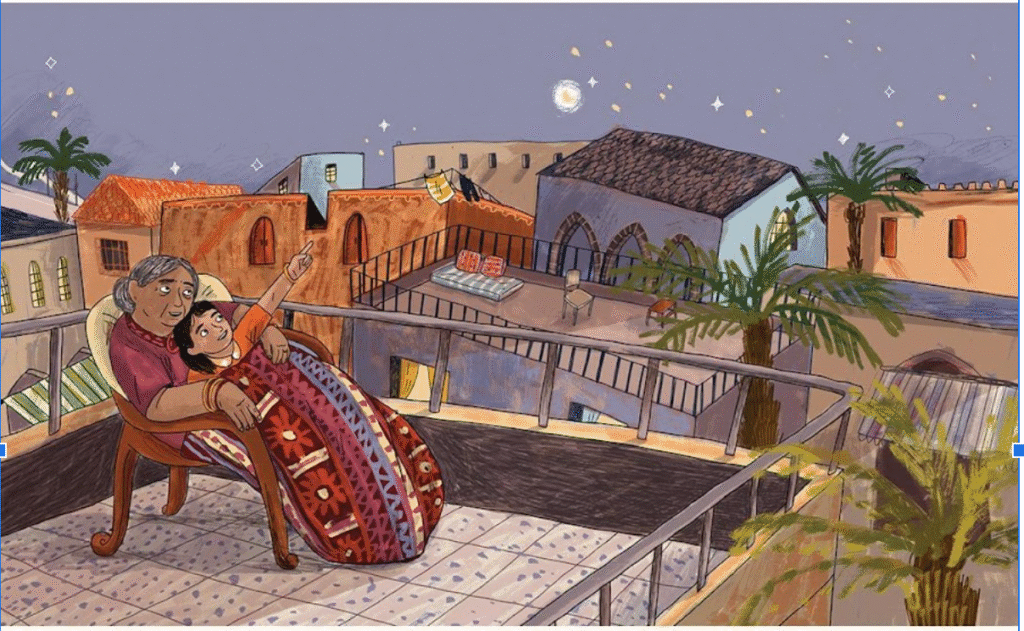

Fortunately, Noa Kelner was a dream illustrator with Mizrahi grandparents, who researched intensively, and artfully portrayed Jewish Baghdad with all its earthy tones, Persian carpets, and palm tree beauty. She even magically captured how Iraqis traditionally slept on their roofs to stay cool in summer with Nana Aziza and Shoham sitting together under the stars in the book’s most beautiful spread. I created metaphors like rolled grapevine leaves that my grandmother used to make — and that Iraqis call yabragh — and the bittersweetness of leaving being like etrog jam. The image of white clouds surrounding the airplane like angels’ wings and the reference to singing Psalms reflect my Iraqi family’s deep belief, a faith typical of Middle Eastern Jews, who are very traditional and connected to their heritage.

Iraqi Jewish life was beautiful. The turning point is the displacement: having to leave with nothing more than one suitcase per family. I grew up with the story that my family couldn’t take any of their valuables with them, including all their jewelry. My aunt, after whom Shoham is named, was seven years old when she, her parents, and four siblings, including my father, departed. She wore a gold turquoise ring, which the airport official insisted needed to be handed over. My aunt was outraged and threw the ring at the official in protest. I wanted Shoham to have a different story.

The hard part was the landing — in Israel, in the ma’abarah, the refugee tent camp. I originally wrote about the harshness of the landing, but I edited it out to make it softer for children, keeping just the hard bump of the plane touching down.

How do you portray refugee tent conditions in illustrations for children? Noa illustrated a tender picture. Still, I tell the truth of how difficult tent camp life was, but I also told the truth of my family’s faith, the Middle Eastern Jews’ comfort — that at least they had each other, and they were in the Promised Land, following the Israelites’ journey through the desert and tents, eating pita like they ate matzah.

I wanted to give Shoham a happy ending. I wanted her to remember where she came from. I wanted to give her the closure and emotional processing that my family — and Iraqi Jews — didn’t have. That maybe only I, as an Iraqi Jew one generation removed, could put into words.

My aunt said she wore her Iraqi bangles proudly in Israel, even though other Iraqi women were embarrassed to. I wanted to return that pride and return the bangle to Iraqi girls and women, to remind them of the beautiful Babylonian Jewish culture we come from. A world of bangles and baking and families sitting together, breaking bread. A world of belonging.

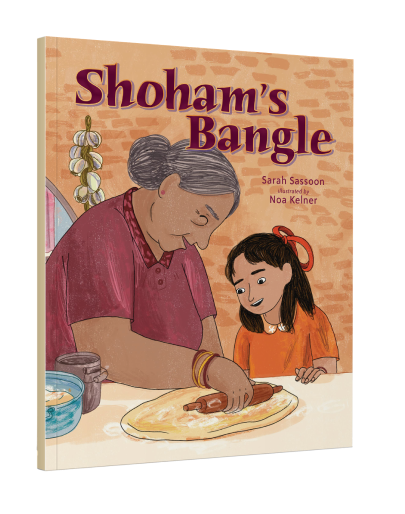

Shoham’s Bangle, written by Sarah Sassoon and Illustrated by Noa Kelner, Minneapolis: Kar-Ben, 2022.

Recreating Lost Mizrahi Worlds

As a children’s book illustrator, I don’t often work on historical books, so when I do, I’m glad for the opportunity and the challenge.

I had to research what Jews who immigrated to Israel from Iraq — mainly from Baghdad — looked like. What they wore, what their homes looked like, the front doors, the kitchen, the furniture, and even the bag in which Shoham brought the pitas (and bracelet) to Israel. I included facts that I liked in the illustrations: For example, because of the heat, people used to sleep on the rooftops, so I chose to illustrate Shoham with her grandmother on the roof under the open sky.

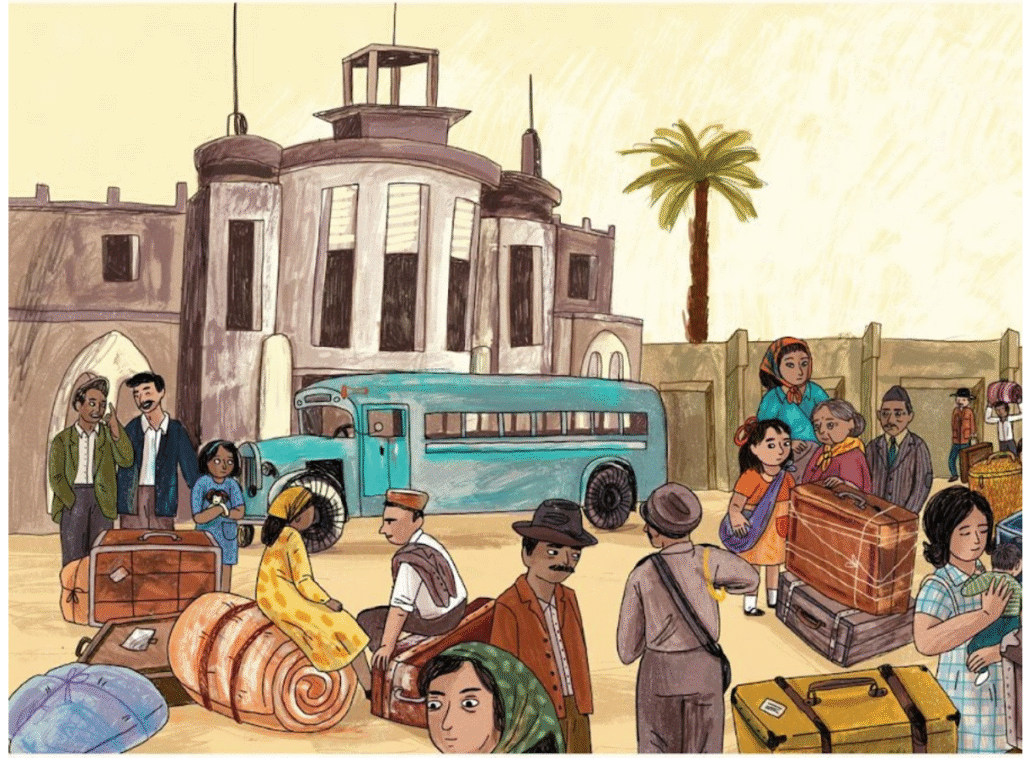

The depiction of the immigration itself — the airport, airplanes, and the ma’abara (transit camp) — was also a significant part of my research, and I based my illustrations on specific historical photographs.

The fig tree appears several times and became an important motif for me, because the family was deeply rooted in Iraq. They had friends, a home, and jobs, fruits that were hard to leave behind. But on the final page, Shoham has her own fig tree, and she plants new roots.

Another connection I made between Iraq and Israel is the picture of Jerusalem that hangs in the living room in Baghdad; in Israel, in the new kitchen, there is a picture of Baghdad.

I live in Israel, and my grandparents on both sides immigrated here from two different ends of the world — one side from Germany and the other from Algeria. Shoham’s family story — leaving behind a whole world and immigrating to Israel — reminded me of my own families and helped me connect to the story with love and a personal perspective.