I grew up in the tight-knit Syrian community of Brooklyn, New York, where being Sephardi was simply the air we breathed. As the daughter of parents whose backgrounds span Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, and Jerusalem, Sephardi identity was deeply woven into my life. I attended Yeshivah of Flatbush high school, and at the time, there weren’t many Ashkenazi students. Interestingly, the Ashkenazi friends I did have were curious about my culture — they wanted to learn about our foods, our pizmonim (liturgical songs), and the unique flavor of our Judaism. I, on the other hand, didn’t know much about theirs. So for most of my youth, I couldn’t have imagined what it would feel like to be a minority.

That all changed when I spent a gap year at Midreshet Lindenbaum in Israel. I was one of just five Syrian girls in a class of 70. The rest were Ashkenazi girls from across the globe — Canada, Belgium, the UK, New York — and I remember being stunned in that first week by how connected they all were. They lived across continents but had grown up attending the same camps and Bnei Akiva programs or, at the very least, had mutual friends. I didn’t even know my own roommates from nearby schools like Ramaz and Frisch. One day, on Ben Yehuda Street in Jerusalem, I bumped into an Ashkenazi friend from Flatbush and told him, “This is the first time in my life I feel like a minority.” Without skipping a beat, he said, “Yeah, that’s how we felt all through high school.” It was a total epiphany.

That year, I immersed myself in Ashkenazi tunes, foods, and tefillot—and I genuinely loved it. The traditions I encountered that year continue to infuse my home. I’ve been teaching Tanakh at SAR High School, a Modern Orthodox coeducational school in Riverdale, New York, for over a decade, and it has never been a secret that I’m Sephardi. I’ve always been the person who chimes in when a practice is described as “the way we do things,” offering, “Well, here’s the Sephardi approach.”

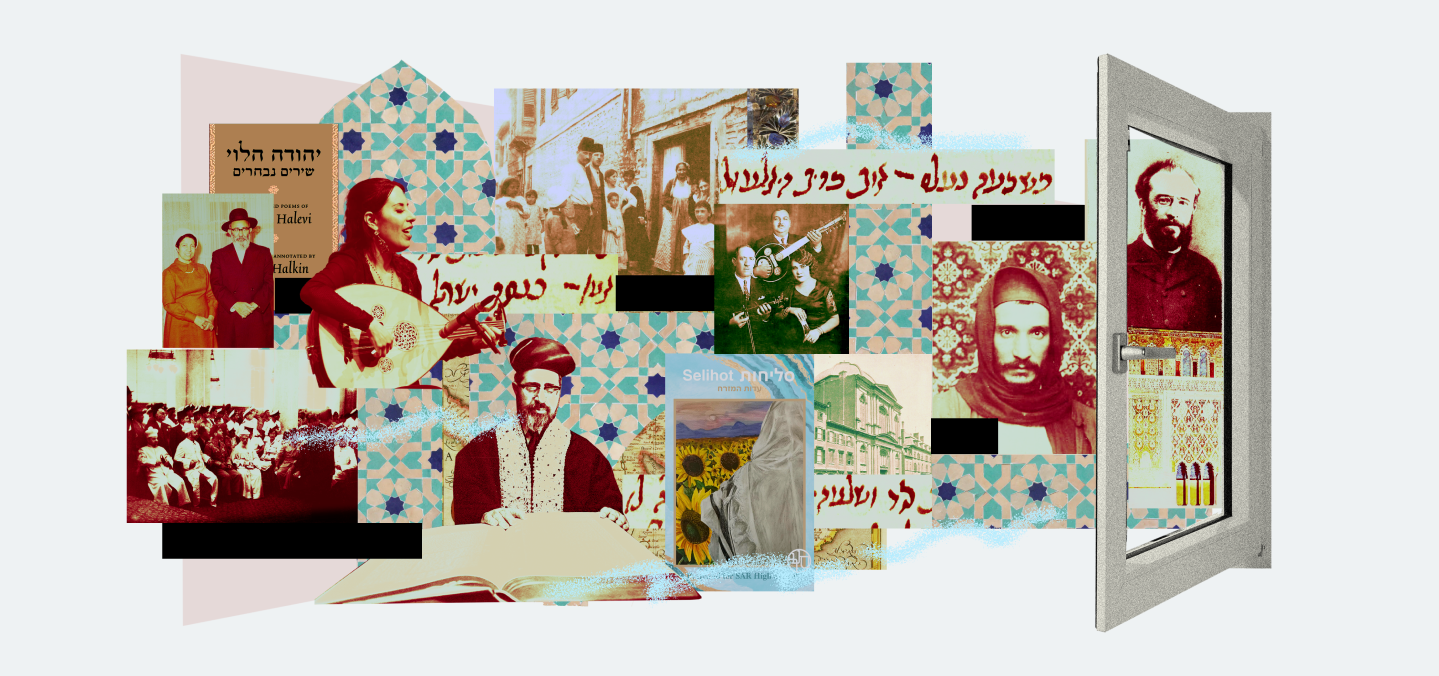

But about three years ago, our principal, Rabbi Jonathan Kroll — after receiving feedback from Sephardi parents — had a visionary idea: to create a role dedicated to cultivating Sephardi life on campus. Having taught at Flatbush in the past, he brought an important awareness of what Sephardi students might need. Alongside my teaching, I now have the privilege of serving as SAR’s Director of Sephardic Engagement. I see my work as both inward- and outward-facing. Inward-facing: creating spaces for Sephardi students to bond, share, sing their tunes, and feel fully at home. Outward-facing: helping the broader school community appreciate Sephardi culture as an essential part of their Jewish story, too. It’s about visibility, representation, and reshaping the assumptions we make about Jewish life.

Some early changes were small but powerful. Each classroom at SAR features a Jewish scholar on the wall — until recently, these were almost exclusively Ashkenazi figures (aside from Rambam). You can now spot many more Sephardi figures all around SAR: Hakham Ben-Zion Uziel, Hakham Ovadia Yosef, Flora Sassoon, Adina Bar-Shalom, the Baba Sali (Yisrael Abuhatzeira), and others. My colleagues have shared that when they teach in the “Sephardi” classrooms, they’re more mindful of the Sephardi students in their classes.

This work can be challenging and isolating at times, but it has also been deeply rewarding and personally transformative. I’m reconnecting to my own heritage and learning more every day about the rich and diverse Sephardi world. ”

We printed Sephardi birkonim (the blessing after meals), incorporated Sephardi melodies into Shabbat, and began serving Mediterranean and Middle Eastern style cuisine at communal meals. One of my favorite initiatives is the Sephardic Culture Club, where we host an array of activities. Students participated in a Hebrew-Persian calligraphy workshop before Purim, explored a range of Sephardi cuisines through cooking demonstrations, and heard “Coming to America” stories from community leaders. We learned about Sephardi life on college campuses and studied Sephardi history. I’ve also partnered with teachers across departments to integrate more Sephardi thinkers and texts into the curriculum. We created a “Sephardic Culture at SAR” Instagram, where students proudly highlight events from the club and spotlight different students’ Sephardi heritage each week (our “Sephardic Star”).

This past school year, we had the opportunity to recite Selihot every morning for a full month. Selihot are traditional prayers of repentance and introspection, chanted in the early mornings leading up to Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. It was beautiful and deeply bonding. While the Ashkenazi minyan had long used a student-designed Selihot booklet, the Sephardi minyan had nothing like this, so over the summer, I sat with my father and curated an abridged Sephardi Selihot text. I then designed a Selihot booklet featuring artwork from our Sephardi students — something our students could be proud of. And they were. It felt like a declaration: We belong here, too.

At SAR, we have an internal educational think tank called Machon Siach. We’ve hosted convenings on antisemitism, Jewish sexual ethics, and Talmud education — and it felt only right to host a day focused on Sephardi life. That’s how M’mizrah L’Ma’arav: Supporting Sephardic Students in Yeshiva Day Schools was born. The goal wasn’t just to showcase SAR’s initiatives. It was to build a network of educators committed to supporting Sephardi students and integrating Sephardi culture more fully into the fabric of Jewish day schools. With more than 50 educators and leaders from 17-plus schools and organizations, it was a day that I hope helped move the needle.

In my opening remarks, I shared how personal — and collective — this work is. I challenged participants to reflect on a few key questions:

- How can we teach about Torah and halakha without including all who contributed to it?

- How can we speak about Jewish unity if our schools don’t represent the full diversity of Am Yisrael?

- How can Sephardi students feel they have an equal seat at the table if their culture is relegated to theme days and food tastings?

I shared a quote from Marc D. Angel, Rabbi emeritus of Congregation Shearith Israel, that continues to ground me in this work:

“We need to be able to speak of the Jews of Vilna and of Istanbul, of Berlin and of Izmir with the same degree of naturalness, with no change in the inflection of our voices.”

That was our goal that day — and it continues to be the goal of this broader work.

Dr. Ronnie Perelis, chair of the Sephardic Studies Department at Yeshiva University, opened the conference with “Sepharad for All” — a crash course in Sephardi history that reminded us: this isn’t just our story — it’s the Jewish story. Dr. Elana Riback Rand presented her research on this topic. Her dissertation: A Minority Within a Minority, surveyed 378 middle schoolers across Ashkenazi day schools. Her findings were striking: Sephardi students reported significantly higher levels of cultural dissonance and lower levels of belonging. Most importantly, she found that Sephardi students’ sense of belonging correlated most strongly with how supported they felt by their teachers. That insight affirms the work we’re doing — to make sure our students feel seen, supported, and celebrated.

Our principal panel featured leaders from several Modern Orthodox coed schools, including The Ramaz School in Manhattan, Yeshivah of Flatbush in Brooklyn, Ben Porat Yosef (BPY) in Paramus, NJ, and North Shore Hebrew Academy in Great Neck, NY. The principals from North Shore Hebrew Academy spoke honestly about shifting demographics and the creative adaptations they’ve made — from new tefillah models to curriculum redesign. Rabbi Yigal Sklarin, who previously worked at Ramaz and is now at Flatbush, spoke powerfully about the deep values embedded in Sephardi families and how those values shape students’ needs. Dr. Chagit Hadar, principal of BPY, reflected on what it means to lead a historically Sephardi school that now has more Ashkenazi than Sephardi students. She shared that graduates of BPY leave feeling comfortable in both Sephardi and Ashkenazi tefillah spaces.

We also explored JIMENA’s Sephardi & Mizrahi Education Toolkit, especially the self-assessment guide designed to help schools reflect on where meaningful change can begin. I was especially moved by schools like Kushner and Luria Academy, where the Sephardi population may be small, but the commitment to inclusion is anything but.

I never imagined I would be doing this kind of work at SAR. It’s still unfolding, and I have many aspirations for the future, including the new Sephardi elective I’ll be teaching next year. This work can be challenging and isolating at times, but it has also been deeply rewarding and personally transformative. I’m reconnecting to my own heritage and learning more every day about the rich and diverse Sephardi world.

I want to stress that Sephardi inclusion is not a DEI initiative. While well intentioned, a Mizrahi heritage day or month will not make Sephardi students feel seen. In fact, I’d argue that such events — especially in predominantly Ashkenazi spaces — can exoticize Sephardi culture rather than affirm it. From my conversations with Sephardi parents, students, and scholars, one thing is clear: What’s needed is real, systemic, institutional change.

My hope is that more schools join this mission. This work matters — not only because it empowers Sephardi students to stand tall in their heritage, but because it allows all of our students — Ashkenazi and Sephardi alike — to see a fuller, truer picture of what Am Yisrael really looks like.