It is with great pride and honor that I introduce JIMENA’s art exhibit illustrating Sephardi and Mizrahi culture in children’s literature. Featuring award-winning authors and illustrators of picture books and graphic novels from across the globe, this exhibit captures the experiences and lost worlds of North African, Middle Eastern, and Sephardi Jewish life and culture for future generations.

Six hundred years ago, over half the Jewish world was Sephardi or Middle Eastern, and yet current Jewish literature reflects an overwhelmingly European experience. There are many reasons for this, among them language, assimilation into Western culture, Euro-centric narratives, and cultural differences in storytelling. And perhaps the main reason for the loss of transmission is historical trauma, the displacement of almost a million Middle Eastern Jewish refugees in the 20th century, including my father and his family from Iraq.

I ask a woman in a Jerusalem coffee shop what she knows about her family’s Iraqi story. “Nothing,” she replies, even though her father spoke Arabic fluently and was a Middle Eastern expert. My family also did not speak about their expulsion from Iraq, nor did they tell the story of the ancient, tapestried Babylonian Jewish life they left behind.

It takes one generation to forget a family story. It takes one displacement to forget that just over a hundred years ago, Baghdad was a third Jewish. One Holocaust to forget that the Jews were the majority of the city of Thessaloniki for centuries. One empire collapsing to forget that Turkey was home to the ancient Jewish communities of Izmir and Istanbul, and was enriched by Sephardi Jews fleeing the Inquisition who were warmly welcomed into the Ottoman Empire in 1492 by Sultan Bayezid II. We have forgotten how he said, “You venture to call Ferdinand a wise ruler, he who has impoverished his own country and enriched mine!”

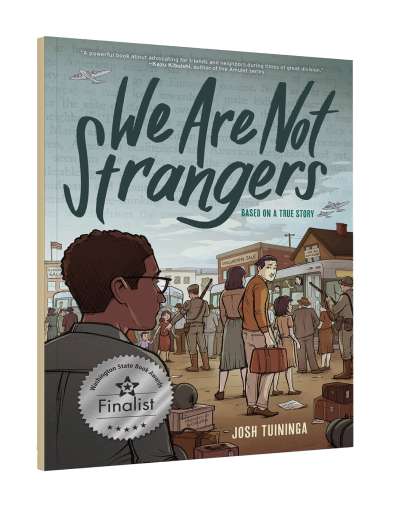

Today over half the Jews living in Israel are of Sephardi and Mizrahi descent. How many know the lives and worlds their parents and grandparents came from? Literature and art allow us to recreate worlds. They are memory keepers of silenced and forgotten stories. Often it is the third generation that follows its curiosity and asks penetrating questions, as Joshua Tuininga in his graphic novel, We Are Not Strangers does. Opening up a vista of intercultural connections and story in wartime Seattle, he asks, “How does a Sephardic Jewish immigrant, with family still overseas threatened by the Holocaust, end up helping out his Japanese American neighbors here at home?”

It is the third generation that is often haunted by ghosts and follow their fading footprints down ancient alleyways, as Carol Isaacs does in her evocative graphic novel, The Wolf of Baghdad, reconstructing Jewish Baghdad and her ancestors’ stories through carefully researched illustrations, helped along by students from Baghdad today who miss their former Jewish neighbors.

It is not enough for history to be researched through academia; it must be accessible. This is what inspired historical anthropologist, Aomar Boum, working with Algerian illustrator Nadjib Berber, to create Undesirables: A Holocaust Journey to North Africa. This graphic novel highlights the lesser known story of the Holocaust in French North Africa, delving into the true stories of Vichy-run forced labor camps and the solidarity between the inmates, highlighting respectful Jewish-Muslim relations.

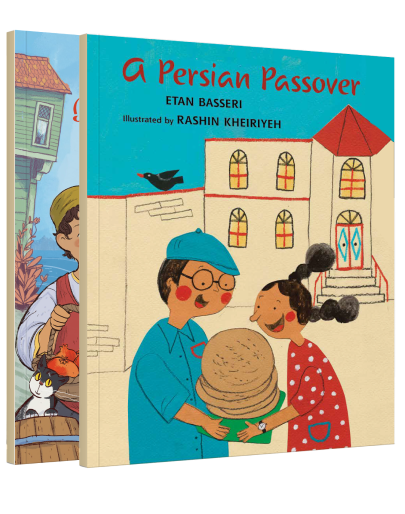

History is never the whole story, either. How do we share customs from a place that no longer exists but that are still practiced in Mizrahi and Sephardi homes today? Etan Basseri expresses how “All children deserve to see themselves and their customs reflected on the page,” and this is exactly what he does through the adventures of his lively characters, lovingly evoked in his picture books, A Persian Passover and A Turkish Rosh Hashanah. The former is the 1950s Iranian world where vibrant Jewish communities lived and some still live, as Iranian illustrator Rashin Kheiriyeh shares. These are not just pictures in oil paints and collage; they are images with depth and emotion reflecting layers of tradition and history, reminding us that “memory and art are connected.” Turkish illustrator Zeynep Özatalay shares the hope that when we introduce children to the neighbors they would have played with on the streets where they lived, their hearts will expand and welcome “the other.”

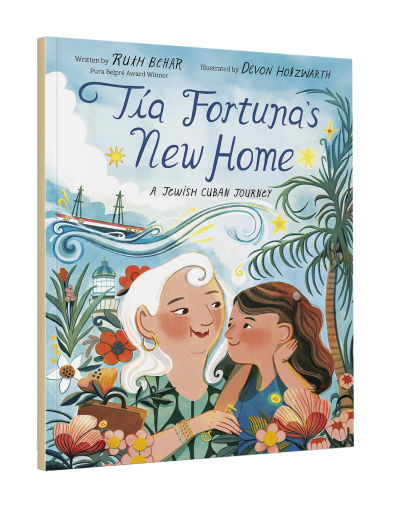

Life was beautiful until it wasn’t. And homes were lost and left behind. The Sephardi and Middle Eastern Jewish stories carry with them the pain of leaving home along with nostalgia for the Jewish worlds they left behind. This is represented with the ever universal symbol of a suitcase in Tía Fortuna’s New Home: A Jewish Cuban Journey.

So much is hidden in a suitcase. As anthropologist and author Ruth Behar expresses, it is the symbol of the Jewish diaspora. But so much else is shared without having to say a word, traditions that carry joy, resilience, and Jewish continuation, which the art portrays, like Sephardi hamsas and evil eye ornaments, family photos, and a mezuza. Perhaps what is strongest are the hands that hold the suitcase of memory together across the generations.

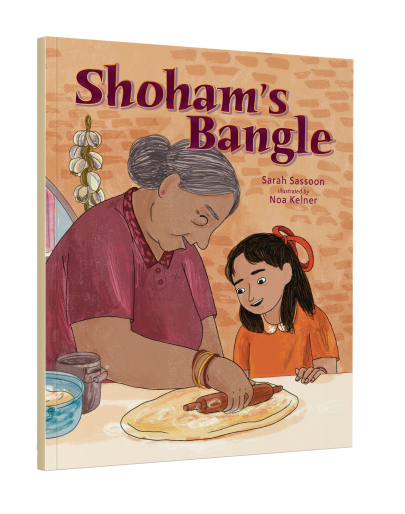

Intergenerational connection is a strong theme in these books. The Middle Eastern and Sephardi story continues because the next generation — often the third — chooses to break the silence and tell their family’s stories. The bangle in Shoham’s Bangle, passed from grandmother to granddaughter, is a symbol of remembering and sharing not just the lost Jewish world of Baghdad but refugee resilience in rebuilding a new life in Israel. This remembering represents Jewish Middle Eastern and North African refugees, and illustrator Noa Kelner conveys her own connection to the story through her Algerian grandparents as well as European grandparents, and how much it mattered for her art to authentically capture the personal story and relationships.

Taking flight is another strong symbol of Jewish displacement, as conveyed in the story of the rescue of 49,000 Yemenite Jews, as told by Tami Lehman-Wilzig in On the Wings of Eagles. Perhaps what is most startlingly felt is the beauty of the Yemenite clothes, home, and culture, as illustrator Alisha Monnin describes. The images represented are exotic and new to us, testifying to how much Jewish Middle Eastern culture has not been imparted with their displacement.

It is the interweaving of text and art, as Erica Lyons shares in Saliman and the Memory Stone, that brings to life the unsung Jewish narratives, such as the Yemenite Aliyah on foot from Yemen in 1881. What adds to the book’s authenticity was Yemenite Yinon Ptahia’s layered illustrations and input into the text highlighting the importance of involving Mizrahi and Sephardi artists in reclaiming their pasts.

The truth about Mizrahi and Sephardi stories is that they have never been truly forgotten. Though their original homes and communities have been uprooted and erased, their lives and traditions are joyously lived and remembered in the dough of ba’aba tamar date cookies baked in Iraqi Jewish homes, in exquisitely embroidered Yemenite costumes worn at henna parties, in sky blue hamsas, and Mazal Bueno lovingly declared at Sephardi festivities, celebrating life. It is echoed in the coexistence of Arabs and Jews working together still today as they once upon a time did across the Middle East and North Africa.

And now the stories live in many homes across the world through children’s books and graphic novels like the ones featured in this special exhibit, connecting generations and worlds. These are our Jewish stories: Forgotten, reclaimed, haunting, intergenerational, and timeless, they define our own narratives in our hearts and homes.