I come from a long line of Babylonian hakhamim, doctors and poets who sang the piyyutim, prayer songs of medieval Sephardi poets like Shemuel ha-Nagid, Yehuda ha-Levi, Moshe Ibn Ezra, Abraham Ibn Ezra, and Shelomo Ibn Gabirol. They sang their poems yearning to return, in ha-Levi’s words, to the tombs of the Patriarchs, the “Carmel’s forest” and Jerusalem’s “lofty peaks.” Their words expressed the psyche of Jews in exile, molding not only our personal and national Jewish identities, but our destinies.

Understanding the medieval Sephardi poets and how they entered the canon of our Jewish conversation helps us to understand the Jewish relationship with Israel between exile and return. In ancient times, the Jewish prophets were our poets; and after the first Temple’s destruction, our poets became our prophets. As Isaac Bashevis Singer declared in his lecture after winning the 1978 Nobel Prize for Literature: “In the history of old Jewish literature, there was never any basic difference between the poet and the prophet.”

This is true of the poets of al-Andalus. They encapsulated the tensions of the Diaspora Jew. On the one hand, they followed the formal traditions of Arabic (pre-Islamic and Islamic) poetry. But on the other, their inspiration and content was deeply embedded in Hebrew scripture, as well as Judean and Babylonian liturgical poetry. As University of Wisconsin Professor Norman Roth observed, it is interesting that medieval Sephardi poets didn’t classify their poems, as modern-day scholars do, into “secular” and “religious” poetry. Their Diwan (collections of their own poetry compositions) were written with a unity of spirit and being, at once enjoying the prosperous cultural, economic and scientific period of convivencia in Spain, and yet acutely aware of their Hebrew origins.

While Ibn Gabirol (1021-1070) wrote “The Redemption,” he never stepped foot in Zion. Yehuda ha-Levi (1071-1141), however, passionately undertook the journey. Legend has it, he was trampled to death at the gates of Jerusalem. Ha-Levi was a famed poet, physician, merchant, theologian, and philosopher living in the splendor of Muslim Spain. Why did he leave? The answer lies in the inspiration for his poetry — ha-Levi felt the call of his ancestors as he writes of Zion, “Your very air is alive with souls.”

Sephardi poets of subsequent eras, such as Shalom Shabazi (1619-1720), a Yemenite, reflected on the Jews’ double exile: “But I, deep in Exile, my feet are sinking,” he wrote, testifying not only to the original exile from Zion, but to his own Exile of Mawza in 1679-1680, where most Yemenite Jews were driven from their homes. Shabazi voices the twofold exile of Diaspora Jews, the vulnerable story of a minority subject to perpetual persecution and displacement.

More than a century later, American writer Emma Lazarus (1849-1887), of Portuguese Sephardi descent, felt the blow of double exile on the other side of the Atlantic while witnessing the rags and ruins of Eastern European Jewry escaping antisemitic Russian pogroms. The plight of the Jewish refugees reawakened Lazarus’s Jewish roots. She translated several of the early Sephardi poets, including Ibn Gabirol and ha-Levi. It is no wonder that their visions of return resound in her poems with biblical clarity: “I open your graves, my people, saith the Lord, And I shall place you living in your land,” she wrote in “The New Ezekiel.” She took up the clarion call for the displaced masses. More than that, she called for the establishment of a Jewish State a decade before Theodore Herzl established the Zionist movement.

Many poems of return were composed in Persia, such as by the little known 19th century Iranian Rabbi and poet of the cities of Rasht and Tehran, Yaghoub ben Paltiel (c. 1830-unknown). In “Eress Ha-Qedoosha,” Rashti repeats the biblical motifs to “Gather your scattered with renewed zeal. Build the city of Zion, the Beit HaMiqdash and the holy abode. Let them sing a new song in Zion.”

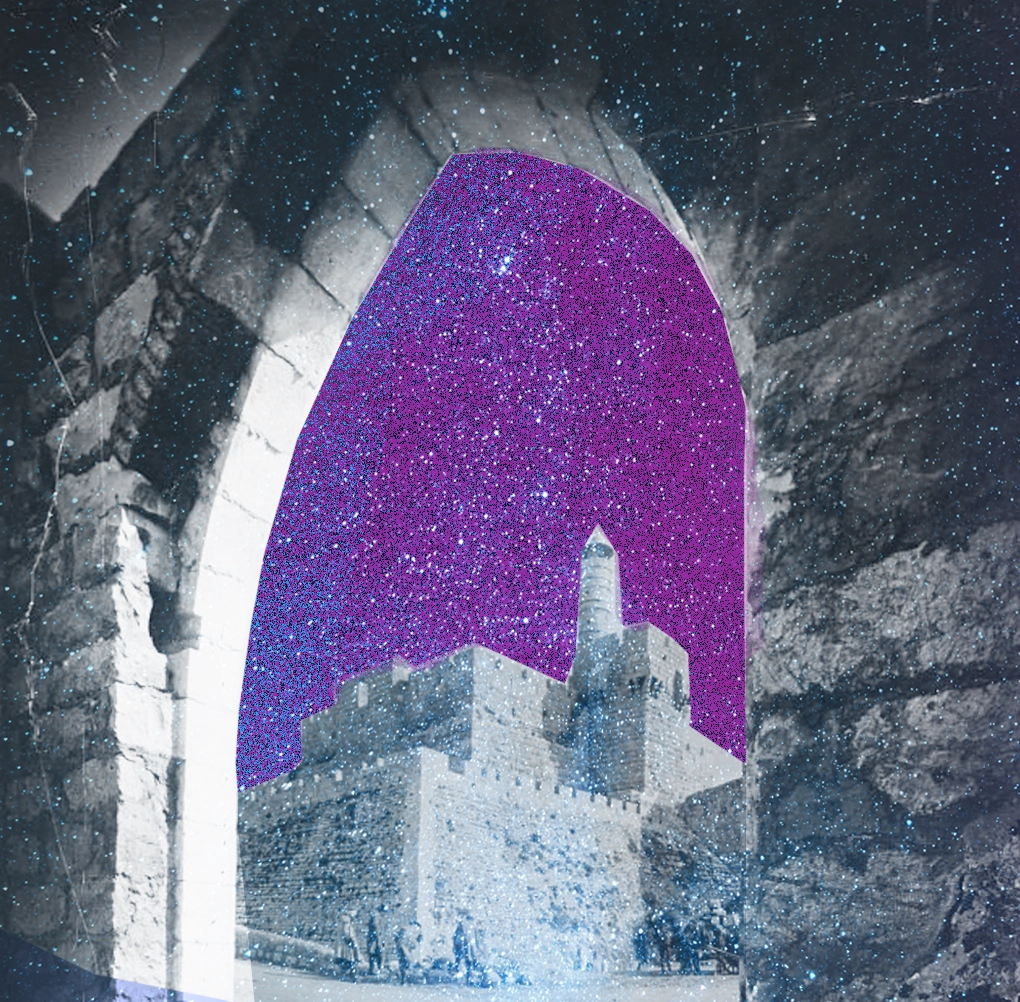

Indeed the poems of return inspired many new songs, with the rise of Zionism and the First and Second Aliyah from Europe (1882-1903 and 1904-1914). Avraham Shemuel Recanati (1888-1980) was a Saloniki journalist, poet and Zionist activist who translated ha-Levi’s poetry into Ladino (Judeo-Spanish) and journeyed to Israel in 1934. Exiled from Spain and Portugal, Sephardi poets traditionally had sung of their longing to return to their Spanish motherland. Recanati symbolized Ladino poetry’s dramatic shift in the late 19th century, which expressed the community’s intense desire to return to Jerusalem. As Recanati’s poem “Yerushalayim” states: “The name itself would have held no special meaning in our youth, had we not yearned for it out of the sense of mystery, of secrecy, of the supernatural.”

But the prophetic pull to the Promised Land was not enough. The gas chambers of Europe and the antisemitic expulsions from the Middle East were the persecution pushes that birthed the State of Israel. Millions of Jews returned.

It was not exactly what the poets had prophesied. And I often wonder if Yehuda ha-Levi had lived in Jerusalem instead of Spain, what poems would he have written? Contemporary Israeli poets continue his legacy, infusing their everyday poems with scripture and prayer. Poets like Erez Bitton from Morocco and Ronny Someck from Iraq encompass the Mizrahi memory of return.

Bitton (b. 1942), hailed as the founding father of Mizrahi contemporary poetry, captures the in-between space of return in his poem “Scaffolding,” where he writes: “On the threshold of half a house in the Land of Israel my father stood.” Driven from their homelands by persecution and discriminated against in Israel, Jews from Arab lands experienced the return to Israel not as a utopian biblical fulfillment, but a jarring reality. “When Did Your Peace Begin?” is the question Ronny Someck (b. 1951) raises in the title of his poem. He captures what many Israelis — those who sought the promised peace of return — ask.

I, too, am a diaspora poet. My family was displaced in 1951 from Iraq, lived in Israel for a time and later moved to Australia, where I was born. Eight years ago, I chose to make aliyah to Israel with my own family. In my poem “How to Speak to Stones,” I seek to harmonize the ideal longing of Sephardi poets with today’s reality. I have learned that the news tells one story and the streets another. My friends at the local café tell me that the poetry of Yehuda ha-Levi and Shelomo Ibn Gabirol is sung by the Turkish-born prince of Israeli rock music, Berry Sakharof. The poems also are still sung in synagogues and at Shabbat tables.

My friends tell me the poets of exile are today’s poets of return. This is what I remember when I sing these beautiful poems with my family on Friday night.

Note: This poetry exhibit and article were conceived and developed in August and September 2023, prior to Hamas waging war in Israel.